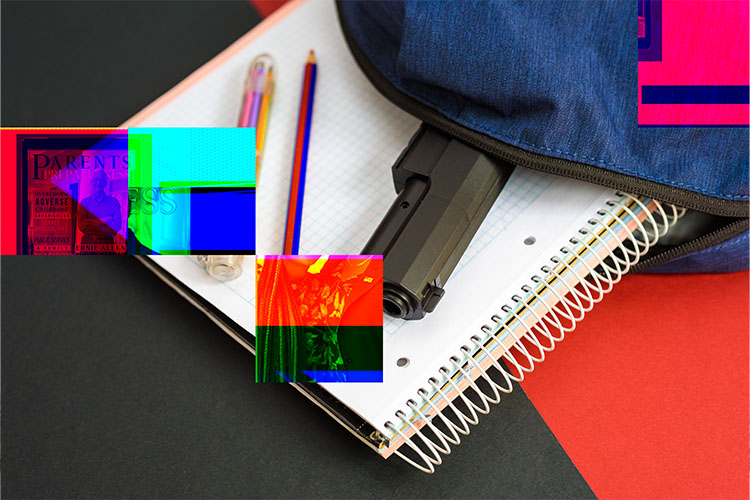

What You Can Do To Reduce The Risk of School Shootings by Christopher Cleary, Ph.D.

Seeing news reports of mass murders occurring in schools is devastating. A recent USA Today article reported that school shootings have reached an all-time high for the second year in a row. Hearing the details of another young person resorting to mass violence causes us to experience several emotions, including sorrow for the victims and their families and anger that these horrific incidents keep occurring. We should not have to fear for the safety of children while they are at school, and we should not feel helpless in the effort to reduce school shootings. Emotional reactions to tragedies are understandable, but fear and anxiety are often wasted energy unless we can channel them into constructive action. Working together, we do have the ability to improve the level of safety in schools. We can take a few reasonable steps to help prevent tragedies.

I must start by saying that the likelihood of a mass-shooting occurring in your child’s school is remarkably low, but despite the odds, mass-shootings do continue to plague our nation. The way to fix the problem is to understand it and then take steps to stop it from occurring or at least lower the number of incidents. Here are some positive, constructive actions that we can take to reduce the likelihood of shooting events happening in schools.

The first step is to improve our understanding of the problem. The students who have committed prior mass shootings did not start out evil. Most were normal kids who, for various

reasons, progressed along a path toward violence and ultimately followed through on their heinous crimes. In a study of past school shootings, the Federal Bureau of Investigation found that the shooters had a variety of motivations for their actions. Some more common motivations were desire for revenge, attention, or recognition, or because they felt bullied or persecuted. Regardless of their motivation, most previous school shooters had done things to make their intentions known prior to the shooting.

Pay attention to the warning signs. Researchers who study the incidents of mass school shootings have found that, in the majority of cases, past perpetrators had provided certain warning signals about their intentions before they resorted to violence. The warning signals were often ignored, misinterpreted, or mishandled. Past shooters have often revealed their intentions though ultimatums, innuendo, predictions of future harm, or by making specific or generalized threats. In many cases, the threats were revealed to a third party.

If you see something, say something. Preventing school shootings does not fall solely on schools, nor does it fall solely on the police or the parents. The only way to make an impact and reduce the threat is to accept that we all have a role. Parents, teachers, relatives, neighbors, or friends may sometimes recognize when a child’s behavior becomes concerning. When we become concerned, we are responsible for promptly reporting the concerning behavior to the school or the police. Deciding to report your concerns about a child may not be an easy decision. We may not want to get involved or get the child in trouble, or we may convince ourselves that our concerns are likely unfounded. We may fear having the child resent us or fear losing their parents as friends, but we must report those behaviors to the school or the police so they can take steps to determine if the child does need intervention. The stakes are too high to ignore. Just imagine if a tragedy did occur and we had the chance to prevent it, but we did not make our concerns known. Once concerns about a student are reported to either the police or to school administrators, they should begin the student threat assessment process. The school and police should work together with psychologists or social workers to determine if the child does or does not present a possible danger to themselves or to others. If the threat assessment team decides the child may present a potential danger to themselves or others, the intervention must begin immediately. Intervention before any criminality is in everyone’s best interest.

Ensure that your school and your police agency are cooperating and working together to prevent tragedy. Attend public forums to speak with your school administrators and with your local police administrators to make sure that they have a good working relationship, that they communicate regularly, and that they share the common goal of providing intervention before any criminal activity. The mere fact that they participate in the threat assessment process does not necessarily mean they are in full cooperation. Schools have traditionally preferred to manage discipline problems internally and would only notify the police when the arrest of a student was unavoidable. At the same time, police agencies concentrate most of their efforts on making arrests after crimes are committed and may not invest a lot of resources in preventing violence in schools. The rising death toll from schools has made those practices unsustainable. These two crucial parts of the student threat assessment process need to work seamlessly together with the common goal of preventing violence and providing intervention to children who might be on the path to violence.

If further investigation by the threat assessment team indicates that the child may be on a path toward self-harm or violence to others, the threat assessment team must work together to get that child help and avoid a potential tragedy. The police should immediately go to the child’s home and enlist the parent’s cooperation to ensure the child does not have access to weapons. If the child or their parents seem unwilling to follow through with counseling, the schools should mandate that the child gets psychological or emotional care to re-enter school.

The threat assessment process should not end there. The school faculty and the police must continue to monitor the student’s progress and watch out for any further warning signals. Once again, this will take serious commitment from both entities, but the stakes are too high for anything less. It might seem that school administrations and police agencies are unyielding monoliths, but they each do their best to be responsive to the needs of the public. Public meetings are an effective way to be heard and let them know the level of commitment you expect. This problem requires a whole-of-community response; we must all do our part. ❦

About the Author

About the Author

Christopher Cleary is an Associate Professor in the Division of Criminal Justice and Homeland Security at St. John’s University in Queens, New York. Before working at St. John’s, he served for over 29 years as a member of the Nassau County Police Department. He retired in 2015 at the rank of Deputy Chief.

He has a Master’s degree in Homeland Security Strategies from the United States Naval Postgraduate School and a Ph.D. in Criminal Justice from Nova Southeastern University. His doctoral dissertation focused on reducing school shootings through the effective use of the student threat assessment process.