Parents and Schools Can Complete the One Two Punch for School Safety By Katherine Schweit

In my monthly newsletter, I deliberately focus on the largest issues, those that present an emergent threat, those that signal a need for new or enforced legislation and those related to desperately needed research.

When the school year is underway, I know thoughts turn to the moment, but I urge those in charge to evaluate the overall quality of a program. Evaluating school preparedness can be done, whether you are a school board member, administrator, teacher or parent. My sure-fire first steps are to ask whether they could answer yes to these seven test questions. I say, be honest and don’t answer yes if what you have is just window dressing.

1. Does your school and district have a comprehensive, and written plan on what school safety means, including physical security aspects and changes that need to be made?

2. Do you know what a threat assessment team is, and do you have a functioning one?

3. Do your students, parents, faculty, and staff know who to report concerns to, including access to an anonymous reporting system? Is it properly and repeatedly advertised in school and in the community?

4. Do you regularly share with students and your community signs to report of individuals who may be under duress, on a pathway to commit suicide, or worse?

5. Do you invite law enforcement and other agencies from the federal, state, and local departments to evaluate your school safety plan, so they know what to do in case of an emergency?

6. Do you have a critical response team who will work with first responders no matter the emergency to ensure they have access to utility cut offs, school diagrams, keys, and information on staff and students?

7. Do you train and run drills several times a year to give faculty, staff and students confidence to respond immediately during an emergency?

I’ve heard feedback that this test produces a worse score than expected. That’s ok. Remember these large undertakings and any step toward safety is a good step forward. To improve a district test score. Consider dividing these efforts up among others, asking who can take the lead. Include the school resource officers, the parent/teacher groups, and local civic groups if available.

Many resources are available, including my newsletter and podcast, to help understand what behaviors of concern should be reported to the school, law enforcement, and anonymous reporting systems. Your school counselor or county mental health providers might be able to shed light on good information to share.

Last year, I shared here how one of the larger challenges that looms is to talk to children about targeted violence and train students. It’s natural for adults to want to protect children and sometimes that means keeping information from them. But students today are aware that school shootings can occur, and silence just adds to their stress.

Instead, I urge each district to work with school resource officers to run non-scary but informative drills three times a year for the students and staff. Many schools mandate some version of active shooter safety training, but often parents are unaware of the training content. The schools don’t share the content with parents, mistakenly believing that school safety details are somehow secret. I’m not suggesting that schools disclose building blueprints, locking codes, and extensive details of their run, hide, fight plans, but there is a middle ground.

Share with parents what you are telling the children and provide them with fact-based talking points to discuss concerns, while reducing their stress and the anxiety a child may begin to feel. Training children in safety shouldn’t involve scaring them.

Of course not. Training doesn’t mean traumatizing.

People who think so perhaps misunderstand what good training for children looks like. They fear children will be scared by the sound of gunshots, the sight of blood, and people running. We don’t train children to avoid streets by showing them pictures of mangled children run over by cars.

Teachers know how to use age-appropriate language to inform and educate without creating fear. Training children focuses on their behavior, empowering them to take part in their own safety. My co-podcaster, Sarah Ferris, was very much against training children when we began our first season of Stop the Killing podcast, but she has quite changed her mind. In each episode we talk about a shooting, what went wrong, what signs were missed about the shooter, and how we can all be better prepared.

Sarah came to appreciate that training for the scariest but rare occurrence of targeted violence is more about teaching children to follow directions immediately and listen, be quiet, be brave when they are scared, and even move to safety if they are in a dangerous place. Isn’t this the same checklist of training tools adults use to prepare children to respond when there is a fire, lightning storm, or even a tornado? The message to children is all the same: listen to the adults around you, follow directions, and get to a safe location. One often overlooked benefit to training is the opportunity to assure children about the rare nature of shootings in schools. We tell children fires and tornadoes are rare, but it is wise to be prepared just in case.

School districts that work with parents to share safety planning for any potential man-made or natural disaster provide the best one-two punch against potential threats. School officials view children’s safety from inside a school’s four walls and parents provide the complementary outside view. Training and drills are just one part of that safety plan. If you’ve already developed quality training and are running drills a few times a year, everyone on the safety beat can answer yes to question number seven and move on to one through six. If not, get to it. ❦

About the Author

About the Author

Katherine Schweit is an attorney and retired FBI special agent who created and led the FBI’s active shooter program after the horrible tragedy at Sandy Hook Elementary School.

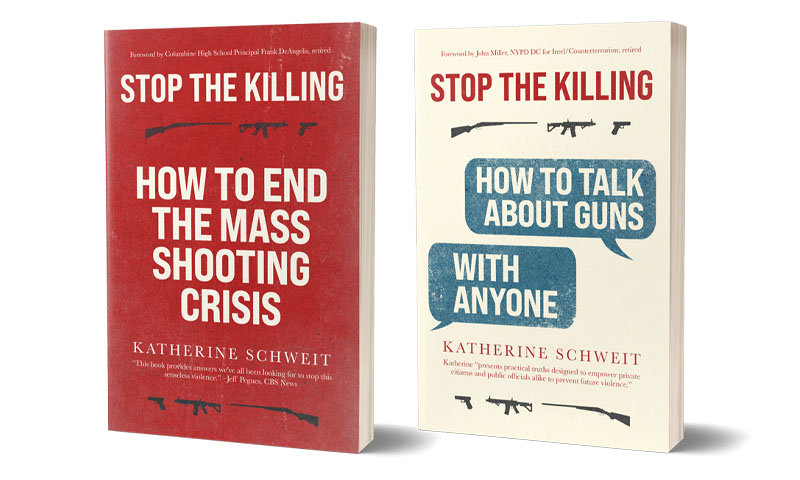

She joined a White House team working on violence prevention matters led by then–Vice President Biden. She is the author of Stop the Killing: How to End the Mass Shooting Crisis and How to Talk About Guns with Anybody. She hosts a podcast in its 4th season called Stop the Killing.

Bookending her time at the FBI, Ms. Schweit worked as an assistant state’s attorney in Chicago and director for security training for a Fortune 300 company. Ms. Schweit brings these public/private best practices to her consulting business, Schweit Consulting, which span from Fortune 100 companies to small private schools, to the government of New Zealand.

She the author of the FBI’s seminal research on mass shootings, “A Study of 160 Active Shooter Incidents in the United States Between 2000 and 2013,” and was part of the crisis team responding to shooting incidents at the Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Pentagon, and the Navy Yard in the Washington, DC, area. She shares free best practices and research through her website and regular newsletter found at katherineschweit.com.

A one-time print journalist she has published extensively, including opinion pieces in the New York Times and Chicago’s Daily Herald. She is an executive producer on the award-winning film, The Coming Storm, widely used in security and law enforcement training throughout the United States and by the U.S. State Department worldwide. This work earned her a second US Attorney General’s outstanding contributions award.

She is a recognized expert in mass shooting and active shooter matters, crisis response, workplace violence, and corporate security policies and often is asked to provide on-air television commentary when tragedy occur. She regularly speaks to professional, government, and private organizations.

She is a member of the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals, the International Association of Chiefs of Police, the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety, the local and national chapters of societies supporting retired FBI Special Agents.

She is an adjunct faculty at DePaul University College of Law and Webster University. She has two daughters and lives in Northern Virginia, outside of Washington, DC. She can be reached through schweitconsulting.com.